Amendment 4

AMENDMENT 4:

Voting Rights Restoration for Felons Initiative

Amendment 4 was designed to automatically restore the right to vote for people with prior felony convictions, except those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense, upon completion of their sentences. Sentences include prison, parole, and probation. As of 2018, people with prior felonies never regain the right to vote in Florida, until and unless a state board restores an individual’s voting rights. Under Gov. Rick Scott’s (R) administration, convicted felons must wait five or seven years, depending on the type of offense, after the completion of their sentences to request that the board consider the restoration of their voting and other civil rights

As of 2018, Florida is one of four states where convicted felons do not regain the right to vote, until and unless a state officer or board restores an individual’s voting rights. This felon voting law was part of the original Florida Constitution of 1968—the state constitution active in 2018—as well as the state constitutions of 1885 and 1868. On February 1, 2018, U.S. District Court Judge Mark Walker ruled Florida’s process for the restoration of voting abilities for felons unconstitutional, saying it violated the First Amendment and the Fourteenth Amendment.

The exact ballot summary language reads:

“This amendment restores the voting rights of Floridians with felony convictions after they complete all terms of their sentence including parole or probation. The amendment would not apply to those convicted of murder or sexual offenses, who would continue to be permanently barred from voting unless the Governor and Cabinet vote to restore their voting rights on a case by case basis.”

BACKGROUND

CONVICTED FELON VOTING LAWS

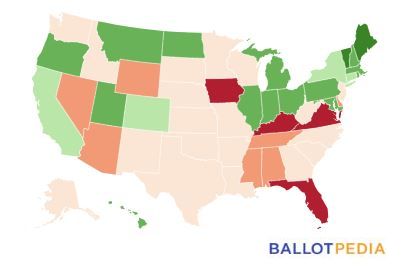

Key: (1) Dark Green–convicted felons always retained the right to vote; (2) Medium Green–right to vote after prison term completed; (3) Light Green–right to vote after prison term and parole completed; (4) Light Red–right to vote after prison, parole, and probation completed; (5) Medium Red–certain felons never regain right to vote; (6) Dark Red–no felons regain right to vote.

As of 2018, Florida is one of four states—the three others are Iowa, Kentucky, and Virginia—where convicted felons do not regain the right to vote, until and unless a state officer or board restores an individual’s voting rights. Amendment 4 was designed to restore voting rights for convicted felons, except those convicted of murder or a felony sexual offense, upon the completion of all terms of sentence, including prison, parole, and probation.

Of the 50 states, two states—Maine and Vermont—do not rescind the right to vote for convicted felons, allowing them to vote while incarcerated; 14 states and Washington, D.C., restore voting rights upon completion of a prison sentence; four states restore voting rights upon completion of prison and parole time; 19 states restore the right to vote after prison time, parole, and probation are completed; and seven states have systems where certain felons, based on the type or number of crimes committed, regain the right to vote.

HISTORY OF FELON VOTING LAWS IN FLORIDA

Section 4 of Article VI of the Florida Constitution, which provided that persons convicted of prior felonies could not vote, was part of the Florida Constitution of 1968—the state constitution active in 2018. Section 4’s provision on the voting rights of felons carried over from the two preceding state constitutions, the Constitution of 1885 and the Constitution of 1868. In 1968, voters approved a legislative referral to keep the provision in the new Article VI, with 55.71 percent voting in favor.

The state’s first constitution, which was enacted in 1838, did not provide that persons convicted of prior felonies could not vote. However, the constitution did empower the Florida State Legislature to revoke the voting rights of people who committed infamous crimes.

As Amendment 4 would provide for the restoration of voting rights to certain convicted felons upon the completion of their sentences, the measure would be amending a constitutional mandate in place since 1868.

In addition to losing the right to vote, convicted felons in Florida lose the ability to hold a public office, sit on a jury, or possess a firearm.

JOHNSON V. BUSH (2005)

On April 12, 2005, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit upheld Florida’s felon disenfranchisement law as constitutional and not violating the Voting Rights Act (VRA).

Plaintiffs contended that “racial animus motivated the adoption of Florida’s criminal disenfranchisement provision in 1868,” according to the court. While criminal disenfranchisement existed in Florida since 1838, plaintiffs said “the scope of such disenfranchisement was significantly expanded in 1868, after the Civil War… to restrict the voting rights of Florida’s newly freed black population.” According to the plaintiffs, the provision had “a significantly disproportionate impact on African-Americans, particularly black men.” Plaintiffs said the provision violated the Voting Rights Act and U.S. Constitution.

The Eleventh Circuit disagreed with plaintiffs, arguing that criminal disenfranchisement, passed as a statute in 1845, preexisted at the time when African-Americans had a right to vote and that the constitutional convention that crafted the 1868 constitution was multiracial. The court also decided that Florida re-enacted the felon disenfranchisement provision of the state constitution in 1968 for race-neutral reasons and that “Congress never intended the Voting Rights Act to reach felon disenfranchisement provisions.”

HAND V. SCOTT (2018)

On February 1, 2018, Judge Mark Walker of the U.S. District Court for Northern Florida declared Florida’s process, which involves an Executive Clemency Board, for restoring voting rights for felons unconstitutional, saying the process violated the First Amendment and Fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. He stated, “It is the Board’s process to restore voting rights that this Court finds unconstitutional.” The order did not rule Florida’s requirement of felon disenfranchisement unconstitutional. Judge Walker said, “A state may disenfranchise convicted felons. A particularly punitive state might even disenfranchise convicted felons permanently. But once a state provides for restoration, its process cannot offend the Constitution.” The Fair Elections Legal Network, representing nine felons, brought the case against Gov. Rick Scott (R).

Judge Walker cited a quote from Gov. Scott, who said “We can do whatever we want” at a board hearing, throughout his ruling. The judge described the process for restoring voting rights for felons as subjective, arbitrary, and discriminatory. He said, “When a scheme allows government officials to “do whatever [they] want,” viewpoint discrimination can slip through the cracks of a seemingly impartial process.” He stated that possible discrimination in the process violated felons’ right to free association and free expression. He also stated that the lack of time limits in processing and deciding applications for the restoration of voting rights could lead to discrimination and violate the First Amendment. The judge said the process violated the Fourteenth Amendment because the executive clemency process in Florida requires “act[s] of grace” that, according to the ruling, “courts historically have avoided.”

Judge Walker upheld the five-year and seven-year waiting periods before felons can request the restoration of voting rights as constitutional. As the “state uniformly applies the waiting periods to all convicted felons,” he said, “this application [process] poses little risk of viewpoint discrimination.”

The judge stated, “Having determined that Florida’s vote-restoration scheme is unconstitutional, this Court must determine the appropriate relief.” He asked the parties involved to suggest remedies by February 12, 2018.

The office of Gov. Scott responded to the ruling, stating, “The discretion of the clemency board over the restoration of felons’ rights in Florida has been in place for decades and overseen by multiple governors. The process is outlined in Florida’s Constitution, and today’s ruling departs from the precedent set by the United States Supreme Court.”

On February 12, 2018, Florida Solicitor General Amit Agarwal told the court that the Executive Clemency Board, not the judge, should be responsible for coming up with a process that meets constitutional requirements. Agarwal said, “There is no reason to upend the state’s constitutional and statutory framework.” Fair Election Legal Network, which brought the case against Gov. Scott, told the judge that voting rights restoration should occur for felons following the completion of a waiting period set in state law or administrative rules. The group said, “Such an order will effectively eliminate the requirement for ex-felons to affirmatively apply for restoration and eliminate the state’s obligation to investigate each ex-felon in the state of Florida prior to making what this court has found must be an objective determination made in a timely fashion.”

On March 27, 2018, Judge Walker ordered the state to develop a new method for deciding how ex-felons regain the right to vote. He gave the governor and board until April 26, 2018, to come up with a new method. Judge Walker did not order specific rules, stating, “This court is not the vote restoration czar. It does not pick and choose who may receive the right to vote and who may not. Nor does it write the rules and regulations for the executive clemency board.”

Gov. Scott announced that he would appeal the ruling to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit. John Tupps, a spokesperson for the governor, said, “People elected by Floridians should determine Florida’s clemency rules for convicted criminals, not federal judges. This process has been in place for decades and is outlined in both the U.S. and Florida constitutions.”On April 25, 2018, Gov. Scott asked the Eleventh Circuit to change the deadline that Judge Walker gave the cabinet to come up with a new method. The Eleventh Circuit concurred with Gov. Scott’s request, staying the lower court’s ruling.

EXECUTIVE CLEMENCY BOARD

In Florida, the right to vote can be restored for convicted felons with the approval of the Executive Clemency Board. The governor and members of the executive cabinet make up the board. While the governor makes the final decision as to whether to grant or deny clemency, including the restoration of voting rights, at least two members of the board need to join the governor to grant clemency. Under rules enacted by Gov. Rick Scott’s (R) administration, convicted felons must wait five or seven years, depending on the type of offense, after the completion of their sentences to request that the board consider the restoration of their voting and other civil rights.

Under Gov. Charlie Crist, who was elected as a Republican, changed his affiliation to unaffiliated toward the end of his term in office, and registered as a Democrat after his time as governor, the Executive Clemency Board automatically restored the rights of felons who had completed their sentences, paid restitution, and had no pending criminal charges. Gov. Crist’s automatic restoration policy did not extend to felons who were convicted of murder, attempted murder, sexual battery, attempted sexual battery, aggravated child abuse, kidnapping, arson, first-degree trafficking in illegal substances, treason, or other specified felonies. During Gov. Crist’s four years in office, 155,315 felons had their voting rights restored.